Harold Lloyd in Safety Last

Set three guys up over whiskeys to debate the greatest comedian of the silent film era and at the end of the night the guy for Chaplin and the guy for Buster Keaton will still be counter-slurring the relative merits of The Little Tramp and The Great Stone Face, City Lights and The General while the guy for Harold Lloyd will have retired to a vacant corner, murmuring to himself about The Glasses Character and The Freshman and staring wistfully at the clock. He’s wishing the night would end, he knows he’s got no shot, but he’s also holding onto his guy’s best moment.

Because that’s what Lloyd did. Hang on. To the clock. In one of the most iconic scenes in movie history. Watch it on the interwebs if you haven’t seen it or just wait til the next Oscars. They’ll likely have some tribute to “the magic of cinema” or some such that is bound to feature it.

Lloyd’s signature persona was an American everyman called (snore) The Glasses Character who would reappear in various forms: a poor country doctor in “Doctor Jack”, a college kid desperate for popularity in “The Freshman”, a lowly department store clerk in “Safety Last”. That last one, where the clock scene appears, wasn’t the only one to put the everyman high above the crowds or in a frantic chase. The titles alone are suggestive: “Look Out Below”, “High and Dizzy”, “Now or Never”, “Speedy.”

Lloyd was one of the most popular and bankable stars of his era. In the 1920s, he ranked higher than Chaplin on several film fan surveys and his features out-grossed Chaplin’s by a wide margin.

What Happened Next?

Lloyd’s star faded quickly in the 30s. Where the go-getter character resonated in the swinging 20s, it was out of step in the Depression era that followed. And while Lloyd’s speaking voice was not unpleasant, the transition to talkies did him no favors. Something essential about his comedy sprang from the physical, which was both enforced and

The One You Know Better:

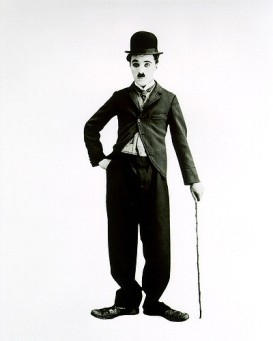

Charlie Chaplin

enhanced by silence. By the mid-40s he had effectively retired to his Beverly Hills mansion. In ’53, he received an honorary Oscar as a “master comedian and good citizen.” The “good citizen” part was seen as a none-too-subtle slap at Chaplin from the Academy for his leftist political leanings in the McCarthyite era.

In his later life, Lloyd was extremely protective of his films, over which he astutely maintained copyright. Not so astutely, he released them to theaters infrequently and demanded high fees for television broadcast. As a consequence, the public became much less exposed to his work than they did to Chaplin and Keaton.

Where Are They Now?

“Safety Last” and “The Freshman” are considered bona fide classics, but you will not find them on many Best of All Time lists where Chaplin’s films (particularly “City Lights,” “The Gold Rush,” and “Modern Times”) and Keaton’s “The General” tend to make frequent appearances.

Popular consensus puts Chaplin over Keaton over Lloyd, with Harry Langdon sometimes thrown in to appease the anti-trinitarians who prefer a “Big 4” to a “Big 3.” But they all have their champions in the critical community and it’s encouraging to see many studies end with an admission that determining greatness on any absolute scale is a fool’s errand, particularly in a field like comedy, where fools predominate.

Afterthoughts

A sustained, low-grade reevaluation of Lloyd seems to have been underway for several decades and while it probably will not re-order the pantheon, it seems destined to continue the debates, whether whiskey-soaked or not, for as long as people argue about such things (aka forever.)